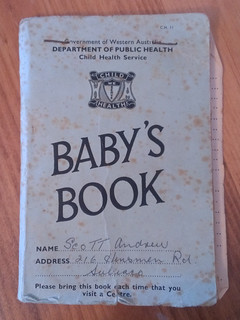

I still have the book that tracked my infant development after I was born. It’s a little time-capsule of medical opinion from a different age.

I still have the book that tracked my infant development after I was born. It’s a little time-capsule of medical opinion from a different age.

At the three months mark, my mum was advised to provide me with fresh fruit juice. These days, the Australian government offers a different medical recommendation:

exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months is the optimal way of feeding infants.

Although, perhaps things will change again soon. The Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy publishes a fact sheet on infant feeding with a different view again:

Based on the currently available evidence, many experts across Europe, Australia and North America recommend introducing complementary solid foods from around 4-6 months.

Similarly, I was told by a colleague that when they were a parent some decades ago, the sleeping recommendation was to place babies on their stomach (I guess to minimise any inadvertent shaping of their heads while they are still soft?). However, the Australian government offers different guidance these days:

Put your baby to sleep on its back and use light cotton blankets.

Well, aside from being confusing when parents get differing advice from their own parents compared with the government, this is actually a good thing: when the medical facts change, the medical community changes its collective mind. And while there’s a good chance that the recommendations aren’t perfect and may change again, at least the new recommendations are better than the old recommendations.

Of course, this is old hat for anyone familiar with scientific method.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t appear to be a similar evolution of knowledge when it comes to recommendations for best managing people. When I have taken courses designed to impart the best new thinking around management, a less useful approach is followed.

There is often an unwillingness to state that prior management recommendations are wrong and should be replaced with better ones. In fact, new techniques have typically been presented to me as new “tools” that can be added to my “toolkit“. This toolkit apparently can grow without limit, and it is largely up to my discretion as to when, where and to whom I should apply a given technique.

I grant that there is difficulty in running experiments needed to show that a particular technique is better than another, and dealing with people is a messier problem-space than dealing with germs or injuries. Also, sure, management science is a relatively new discipline. Still, it feels like a cop out.

I hope that one day, looking at today’s management courseware will seem as quaint as looking at my old baby book.